Manufacturing OEMs are faced with the challenge of building increasingly customized, specialized machines – and getting them up and running as fast as possible. With no time to spend wrapped up in testing, how can they get their machines to market faster? The answer: using simulation and digital twin technology.

We've all been there: You get to the end of a long and frustrating project only to discover it doesn't meet the specified requirements or work the way it was intended. Suddenly, you're back to the drawing board. These situations are particularly devastating when you've just spent months and months building a very complex, very expensive machine. If developers were instead able to test a virtual version of the machine in advance, they could identify potential errors and correct them before the machine is ever built.

When a customer orders a new machine, they want it to be up and performing as expected as soon as possible. Nobody can afford to get to the unveiling of a finished machine, only to discover that it fails to deliver on the original requirements. Neither the machine builder, who has now developed an entire machine for free, so to speak, nor the machine operator, who is now unable to start production until a new machine is built.

Digital machine testing

To avoid ending up in this dead-end street, machine builders rely on simulation. Different simulation tools can be used to create digital twins of individual mechanisms, entire machines, or even complex plants and use them to test all sorts of different manufacturing processes. "A good idea is only good if it actually works in practice," says Kurt Zehetleitner, head of B&R's simulation and model-based development team. "Simulation and digital twins give you the tools you need to make good ideas work – quickly, easily and inexpensively."

A digital twin is an exact digital duplicate of a real machine. It behaves and functions exactly like its sibling. This eliminates the need to build hardware prototypes as the machine is being developed. The real, physical machine is not built until everything is functioning smoothly in virtual form, performing just as the customer imagined it. That saves time and money.

Digitizing an idea

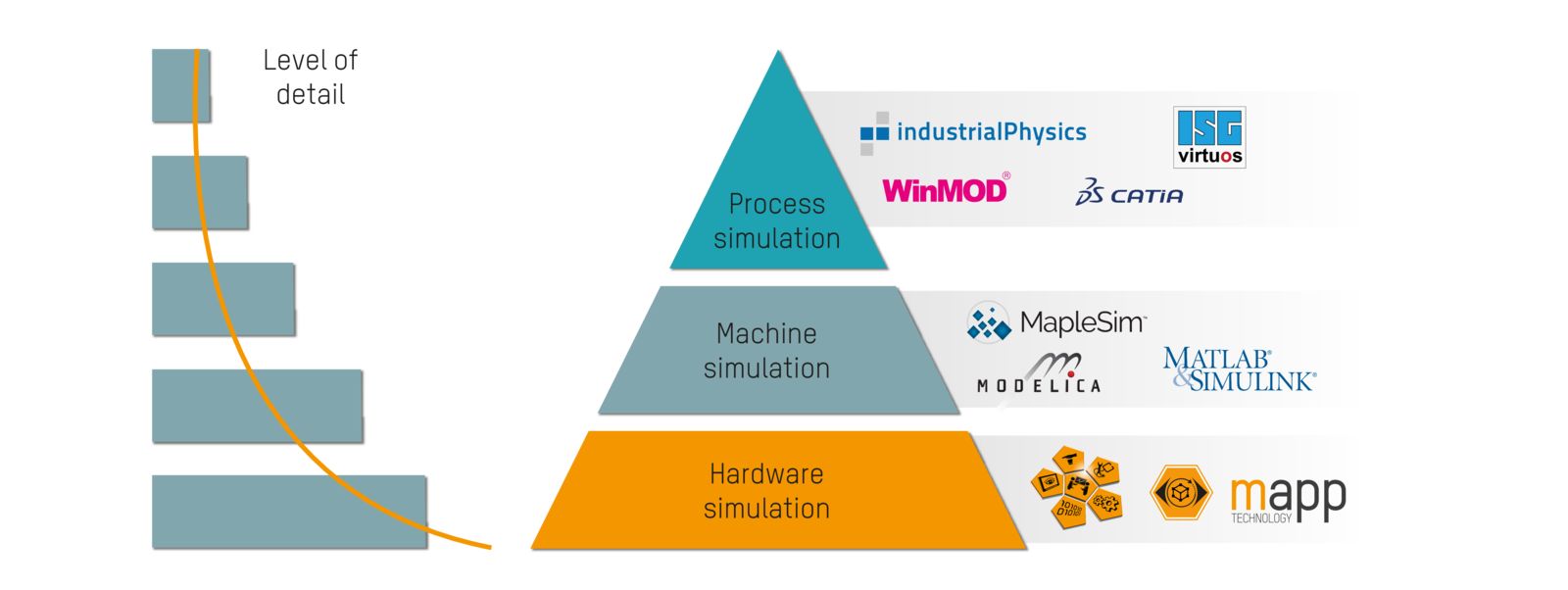

Depending on the task at hand, there are a variety of simulation tools available. B&R makes full use of all the possibilities: "The scope of simulation tools we've built into our systems covers the entire development process from start to finish," says Zehetleitner.

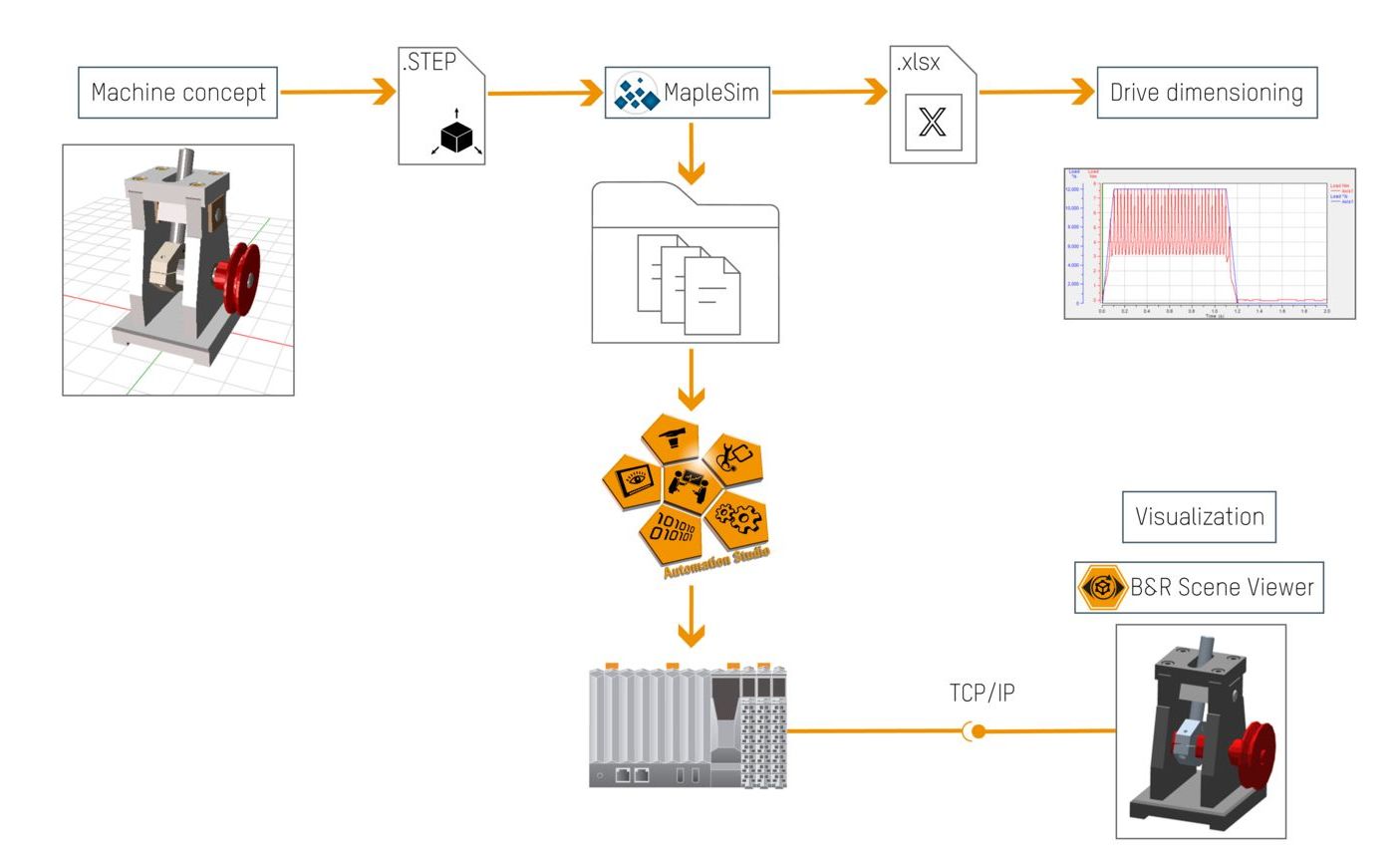

In the earliest phase of development, the focus is on individual functions and mechanisms – the fundamental concepts behind the machine. MapleSim is the ideal simulation tool for that. "We've had very good experiences with MapleSim in this area," says Zehetleitner. "It's a very efficient way to make very detailed models of machine components along with the torque and other forces that affect dimensioning."

When the developer imports the CAD data for a mechanical part into MapleSim, all the information needed to create a digital model comes right along with it. They can easily define which parts should be moveable without having to work directly with all the complex calculations themselves – that's MapleSim's specialty. Movement sequences and pivot points can be defined with a few clicks of the mouse.

Quickly and easily, the developer specifies exactly how the component will be able to move. All the forces that affect the machine are also simulated, so it's easy to test all sorts of load scenarios. Even scenarios that would otherwise consume time and resources or be unsafe or impossible to perform on a real machine. At a glance, the developer can see whether or not the machine can handle a given load.

Selecting components

Once the digital twin of the machine component has been completely set up and all movement profiles have been defined, the next step is to select the corresponding motors and drives. To do this, B&R has coupled MapleSim with the SERVOsoft drive sizing tool. "All of B&R's products are available in SERVOsoft. Once it gets the information from MapleSim, the drive sizing tool recommends all the drives that would be suitable for the model. Undersized or oversized automation components are a thing of the past," explains Zehetleitner.

Parallel development of hardware and software

FMUs can be exported from MapleSim to transfer the model – along with all the equations and CAD data – to B&R's Automation Studio engineering environment. "You're able to develop the software and hardware in parallel before any single part of the machine has actually been built," says Zehetleitner. The data can be easily updated with any necessary adjustments. Since all the systems are interconnected, the digital twin adapts along with it. This process not only saves a ton of time, it also reduces the cost of prototyping.

The developer tests the automation software for the digital model of the machine directly on their laptop with no need for real hardware. Once they are satisfied with the results of the simulation, they can transfer the software to the actual controller. Thanks to B&R Scene Viewer, they are able to view a 3D visualization of the digital twin as they test and optimize the solution's hardware and software components. An actual prototype is not built until every process in the machine is running smoothly. "B&R Scene Viewer also comes in handy throughout the development process for giving the customer periodic previews of how the machine will move when controlled by the machine software. This way, the machine builder can be confident that the final result will reflect the customer's expectations," says Zehetleitner.

New machine generation born from a digital twin

A digital twin doesn't stop being useful once the machine is built and out the door. It can be used throughout commissioning and even later for online troubleshooting. Software updates and potential solutions can be tested first on the digital model – and only transferred to the real machine once they're working smoothly. And beyond that, the digital twin and control software continue to serve as a platform for ongoing optimization of the machine and development of future generations.

Author: Carola Schwankner, Corporate Communications Editor, B&R